Fermat's Last Theorem - Numberphile

Jun 06, 2021A problem worthy of equalization affirms this value by challenging the solution. And such was Fermat's great

theorem

that defied any solution. So when we talk about Fermat's greattheorem

, I think it's good to start with Fermat. Pierre de Fermat was a 17th century mathematician who lived and worked in France; He was not a mathematician, he worked as a judge. He came home at night (and mathematics was his hobby). One night he was working on an equation that looks a little like the Pythagorean theorem, which is X squared plus Y squared equals Z squared. And he was looking for integer solutions to this equation, and there are many, like 3 squared plus 4 squared, 5 squared.This is the integer solution of

A shadow of a doubt is that there were no complete solutions. So it's a little strange because we have an equation

In other words: I know how to prove that this equation has no solution, but I don't have enough space to write it down. And then he died. It was a secret proof that he never wrote down, and after his death his son, Samuel Clémant, I believe, found this book with this note in the margin:

So his son published a new version of that book - Arithmetica - with all of Fermat's little notes printed in the text, and people said: Fermat can prove this, so one by one they discovered proofs every time Fermat stated: I have a proof, there was a proof, except in this example, Fermat's great theorem got its name because it was the

last

one for which no one had yet found a clear proof, because it is thelast

one that. It can be tried, it is the most valuable, it is the most desired. And the more people try, the more they fail, the more beautiful it becomes.And this continues for decades and centuries. Until the 20th century, people were eager to discover what Fermat's test might have been. Was it the widely accepted idea that he could do it or that he was just making it up? I think after that time in the 20th century it became clear that this was a really difficult problem. It's easy to write down the problem statement somewhere. It is easy to explain the problem. But the test is very demanding and probably out of Fermat's reach. Some people think that Fermat was just playing, that it was just a trick he left to torment future generations;

I think this is the least likely. Some people say that he had real evidence and that it was beautiful and elegant and 17th century and that we could find the evidence, but we're just not smart enough. I think that's possible, but unlikely. I think it's most likely that Fermat thought he had proof. Since he worked alone and since he didn't show the proof to anyone, nobody could tell him: look, there's an error, there's something wrong in the third line. And that's very likely, because we know that the next generation of mathematicians thought they had found the proof, and then they published it, and people tore it apart and found errors.

So what we are looking for is not Fermat's proof, which was probably wrong, but rather we are looking for evidence that Fermat was right after all. It has a happy ending. And it begins with a ten-year-old boy, a boy named Andrew Wiles, who was reading a book one day. He grew up in Cambridge. He went to the library, he borrowed the book

But the ten year old doesn't realize what he's getting into, but that's another story. And so he tried it, he talked about it with the teachers, about the problem, he talked about the problem with the high school teachers, then he went to college and talked about it with the college professors. He then does a PhD and is still obsessed with the problem. I think he was almost 40 at the time and a professor at Princeton, and there's something called the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, which we won't go into here, that was proposed in the '50s. Basically, we don't know if that assumption is true or not, but someone put it on the table.

Someone has shown that there is a connection between both assumptions. The bottom line is: if you prove most of the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, you also get Fermat's Grand Theorem for free. So Fermat's great theorem is, so to speak, part of the second conjecture. And Andrew Wiles' childhood passion has been rekindled as he believes the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture is worth trying. He thinks he can bite him. But it's still crazy to try because it's such an ambitious challenge, which is why Wiles hasn't told anyone about it. He worked completely secretly, stopped attending committee meetings, was in the office less and less, and began to concentrate on his problem.

Again, not because it was the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, but because he would obtain Fermat's great theorem. And he worked in complete secret for 7 years, and after those 7 years, he suddenly realized that he had Taniyama-Shimura, and when he had Taniyama-Shimura, he had the proof of the Great Theorem of Fermat. He went to Cambridge, he presented his proof on the whiteboard, it was a three-part lecture, the world applauded, he was on the front pages of the New York Times, he was on CNN, he was everywhere. But the twist to that fairy tale was the fact that the mathematical proof had to be proven.

It needs to be reviewed and published, and while the review process was going on, someone found an error. Wiles thought he could solve it, but the more he tried to solve the problem, the worse it got. And it has become a great shame, they just declare you the greatest mathematician of the 20th century, you are practically a hero, and now you have to admit that you were wrong. And it took a whole year, but at the end of that year, Andrew Wiles and a guy named Richard Taylor were able to do the test. I think it's a bit like the movie Terminator that I talk about a lot, you know, when you think you've defeated the villain, when you kill the Terminator, he comes back to life and you have to fight him once again.

And someone, I think the mathematician Pete Hines once wrote:

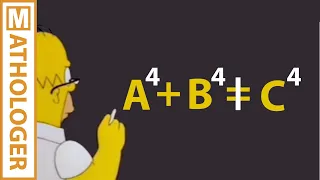

Simon also has a book called Fermat's Great Theorem, it's incredible, I recommend it, link below the video and just this week there is a new book, and the funny thing is that in The Simpsons everything is about mathematics and I think any Numberphile fan will understand. I love it. I'll put a link below the video, but he also interviewed me about Fermat's Great Theorem on The Simpsons, which I think you'll enjoy and I'll upload it to Numberphile soon. But in the meantime, there are a bunch of links down there, I'll link to Wiles' article and a couple other things I think you should see, so take a look.

If you have any copyright issue, please Contact